The Gold Rush Wine Pioneers

In my last post</a> I talked about one of California’s earliest and most colorful wine pioneers, Agoston Haraszthy. Starting in the earlier 1850’s he would just be one of many. Living in California between 1845 and 1865 must have felt much like it has been in China the last 20 years–tremendous change in a relatively short period of time. The Bear Flag Revolt, Gold Rush, California statehood, and completion of the transcontinental railroad all contributed to one of the most incredible mass migrations in history. Just in the period between July of 1848 and April of 1849 it’s estimated the population of California rose from 24,000 to nearly 100,000! The stage was set for California to establish itself on U.S. and world maps.

As I mentioned my post The Mission and its Grape, wine would become the adult beverage of choice for many new Californians despite that fact most of it was lacking in quality. However, a few pioneers were particularly keen on making higher quality wines. Since colonial times Americans had been trying to establish vines and produce wine in the eastern and midwestern U.S. with little success. Finally it seemed California might provide the climate and soils conducive to this quest. However, California was a long way away and for the most part its wine had a poor reputation in comparison to the mature wines of France. That began to change in the mid-1850s when a nasty root burrowing aphid known as phylloxera made its way from the eastern U.S. to France and began ravaging its vineyards. Enophiles in the eastern U.S. were suddenly finding French wine scarce. Market forces began driving higher quality wines in California which had yet to be infected.

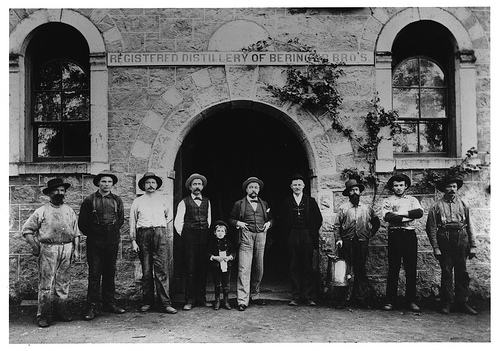

By the 1850s vines were successfully growing all over California. However, when the finer French vines were introduced it was quickly evident they would not perform well everywhere the ubiquitous mission grape was grown. Agoston Haraszthy and his winemaker Charles Krug were arguably two of the first to recognize northern California as a good place to grow these varietals. It was also probably no coincidence that northern California was all a-buzz with new settlers as a result of the Gold Rush. One prosperous gold miner named John Patchett would be the first settler to plant vineyards in Napa Valley. Charles Krug briefly helped Patchett as winemaker before leaving to start his own winery up valley near what is now St. Helena. Krug then hired a German immigrant named Jacob Beringer who, with wealthier brother Frederick, would purchase 215 nearby acres to form Beringer Estate Wines in 1875. Meanwhile, a German Gold Rush brewer Jacob Gundlach decided to follow his father’s footsteps into winemaking and planted vitis vinifera grapes in 1858 arguably releasing his first wine even before Haraszthy. Among a few in other parts of California, these were the earliest pioneers of quality wine in California. However, California was a remote place and despite higher demand the export market for its wine was fledgling at best. That began to change in 1869 with the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

“Easy” gold had run out long before the 1870s, but word traveled slowly and immigrants kept coming. Giuseppe Simi left Tuscany in 1849 to find his fortune. Having limited success, he and his brother Pietro started Simi Winery in Healdsburg, Sonoma County in 1876. Others like Finnish-born maritimer Gustave Niebaum came to California on business after surveying the U.S. Alaskan purchase as consul for Russia (a decision they would later regret). He intended to relocate to France to start a winery, but his new Californian wife objected and he settled for a property called Inglenook near what is now Oakville in Napa Valley. Niebaum took his new winery seriously and quickly replaced the inherited Black Malvoisie grape with many imported varietals including Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec, Chenin Blanc, Riesling, and others.

Despite success stories of these earlier pioneers there were many failures. Captain John Drummond settled in what is now Kenwood, Sonoma County to build his Dunfillan Winery. He imported and planted vines from French Chateaux Margaux and Lafite Rothschild. However, he was unable to sustain his enterprise and sold out to Louis Kunde whose family would form Kunde Winery. Many small wine enterprises like Drummond’s came and went and were never sold, but their individual contributions would later be significant. Even after properties were abandoned and owners moved on, their vines and winery buildings would remain. These so-called “ghost wineries” would be foundations for new wineries established a many as 70 years later.

Phylloxera eventually came to California in the 1860s and crept its way through both counties making it increasingly difficult to maintain vineyards. This was alleviated by the practice of grafting vines in the 1870s and the boom resumed. The 1890s would see new wineries from Italian immigrants Sebastiani and Sbarbono (Italian Swiss Colony) in Sonoma County. During the same period Napa wineries Krug, Beringer, and Inglenook were increasing in size and prestige. By 1900 quality wine was equally produced by both counties, but the seeds of recognized quality out of Napa were sprouting. In San Francisco’s 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition Niebaum’s Inglenook outpaced all other California wineries in awards.

The wine industry seemed in full swing until the depression of 1893 hit the wine industry hard forcing many small producers out of business. Then, just as recovery seemed on the rise, the dreaded 18th amendment in 1920 dealt the final blow from which few wine producers would survive. In my next post we’ll examine the “dark days” from the prohibition in 1920 all the way through the end of World War II in 1945. A period in which Americans would lose their short-lived interest in quality wine developed during the late 1800s and replace it with the miracle of Vine-Glo and the economics of jug wine.