The Prince of Grapes

In our previous chapter I discussed how the Mission grape was the main varietal of winemakers prior to the Gold Rush. Despite making mediocre wine it could be considered a “good starter” grape in that it grew anywhere and was fairly reliable at harvest time. However, it would eventually lose its luster and much of that credit can be attributed to one man.

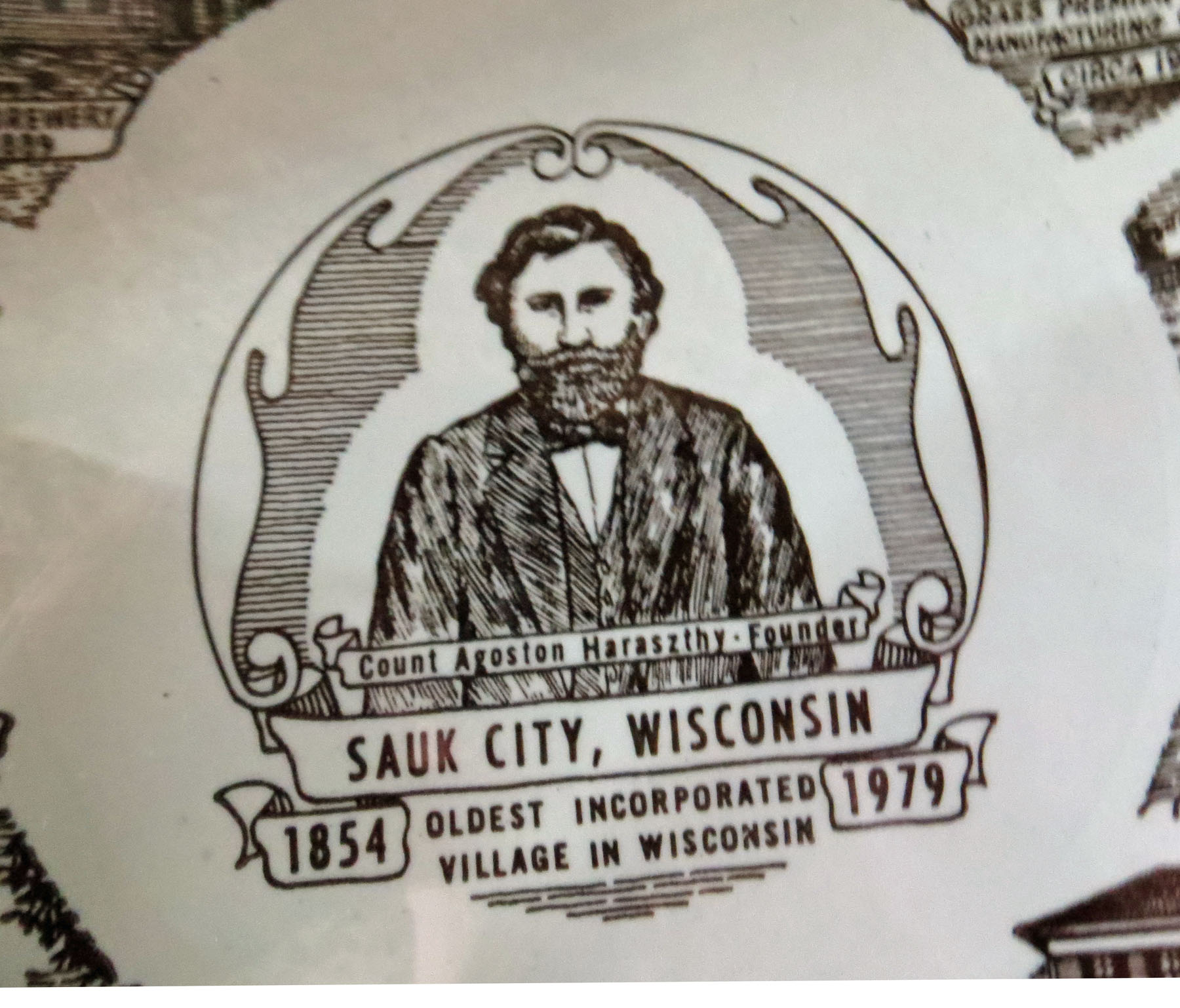

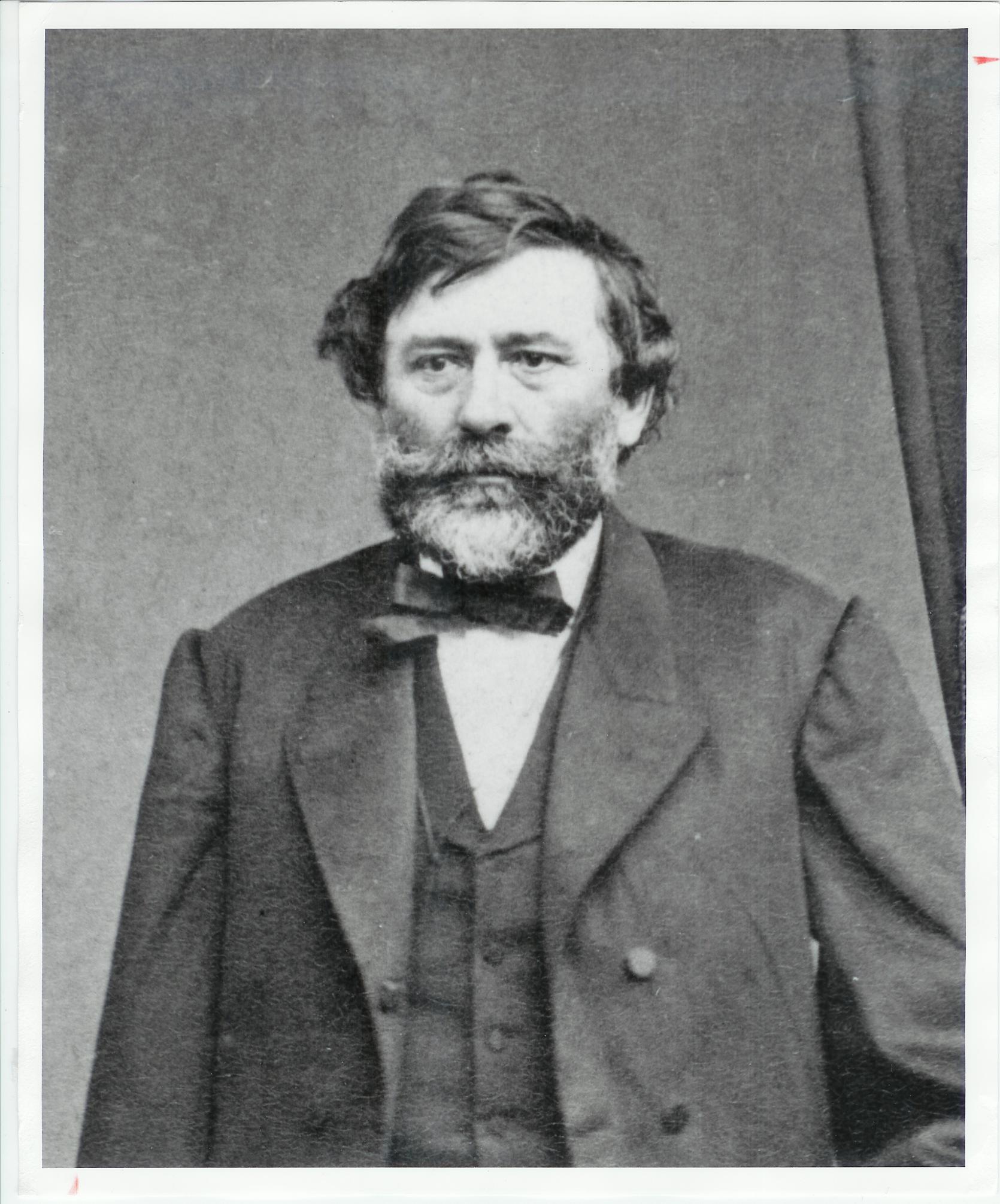

In 1840 a spirited and adventurous Hungarian named Agoston Haraszthy arrived in my home state of Wisconsin and immediately started making a name for himself. To call him a character would be an understatement. A descendant of Hungarian aristocracy, he frequently referred to himself as “Count” or “Prince” even though he was neither. After traveling about the eastern U.S. he returned to Hungary to fetch his family. The first Hungarian to permanently settle in the U.S., he established the first incorporated town in WI and operated the first steamboat on the upper Mississippi. However, in 1849, partially under direction of his doctor (he was an asthmatic), and partially because he was in debt, the family headed west to California. Once here, Haraszthy quickly assimilated into California society; first in San Diego as a marshall and county sheriff, then in Sacramento as an assemblyman. At the end of his term he decided to relocate to San Francisco. There he was appointed assayer of the new San Francisco Mint. However, after an embezzlement scandal of $150,000 (for which he was eventually exonerated), he relocated to Sonoma. For our purposes, this is where the story gets interesting.

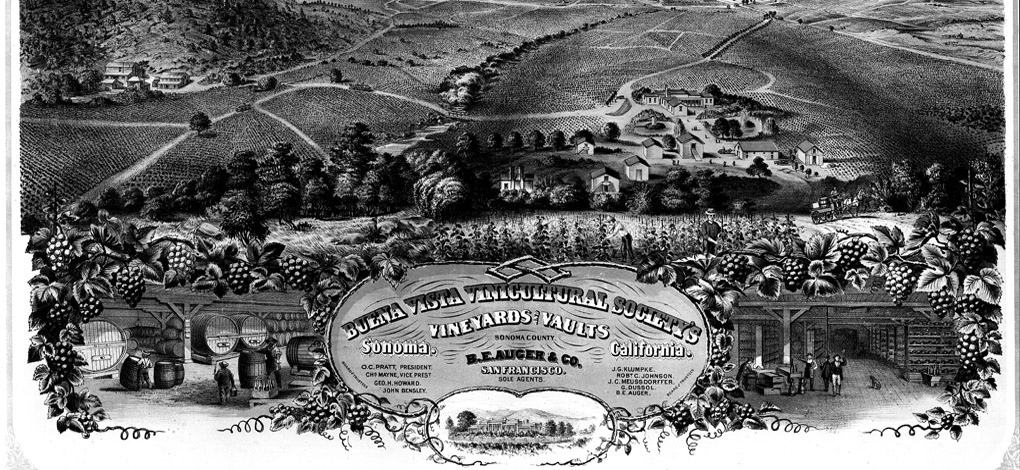

Agoston shared his father’s passion for winemaking and planted grapes just about everywhere he lived in the U.S. He doubled Sonoma’s wine acreage by planting 25 acres in 1857 on plot of land he called Buena Vista just east of the town of Sonoma. The next year he planted another 60. He experimented with many winemaking and viticultural techniques like hillside planting, redwood barrel fermentation, underground storage, and a vineyard row management he called “layering.” Eventually, he wrote a book called Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-Making which was generally well received.

However, his biggest contribution to the California wine industry was his preference for the better European varietals.– In 1861 he pulled some strings and got the California state legislature to commission him to travel about Europe to collect grape vines. During his lavish tour he gathered over 100,000 cuttings of 350 varietals. On his return, partially because of his expense report, the state government refused to reimburse him and Agoston was forced to sell and propagate the vines himself. Thus, was the end of the reign of the Mission grape. In the beginning, Agoston’s wine venture was a huge success. In 1863, he incorporated the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society, and with the help of investors, expanded his winery and sold wine as far as the east coast. However, success was fleeting when phylloxera found it’s way to California in the 1860s and drove Agoston to bankruptcy in 1867.

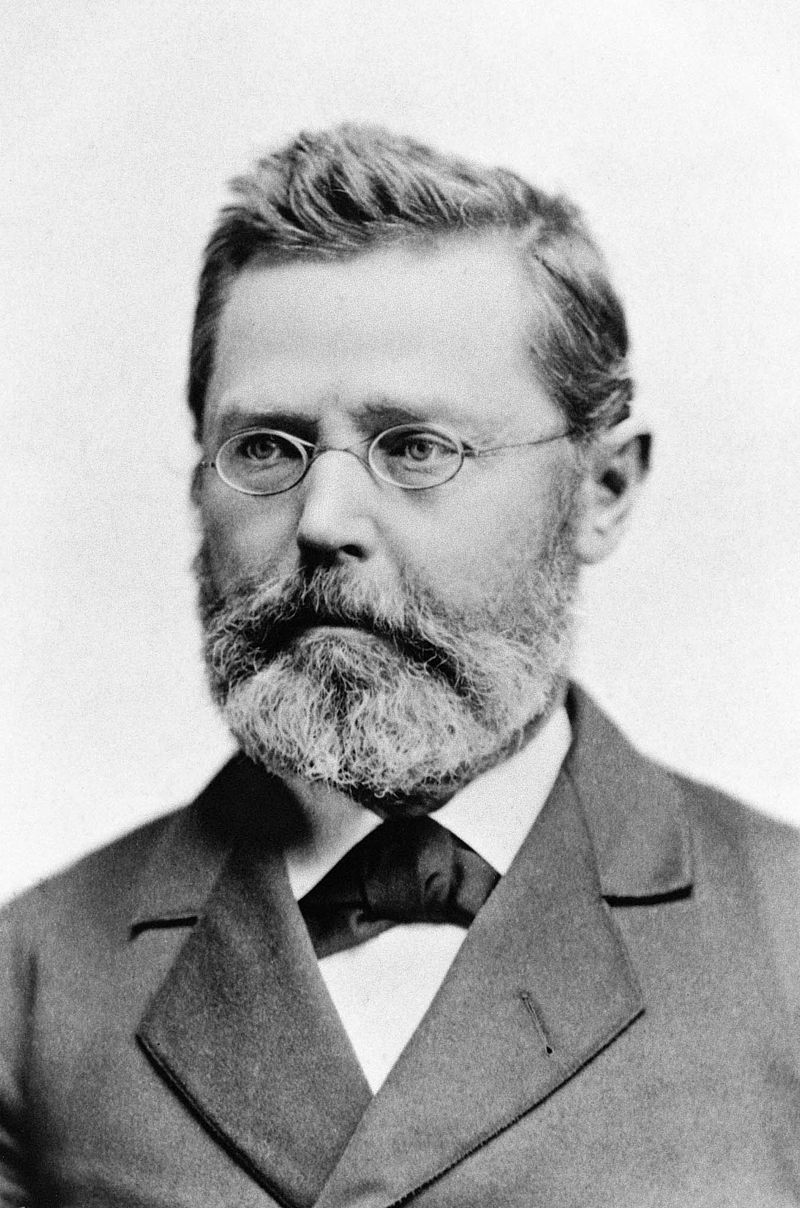

Despite Agoston’s failure, new seeds were firmly planted for the California wine industry. Thanks to the Count many vitis vinifera varietals found there way into Sonoma and Napa County vineyards. Agoston’s initial success spurred a spirit of experimentation amongst other winemakers. His vinicultural society brought about more collaboration within the industry. His sons would eventually become members of the newly formed California State Board of Viticulture. His son Arpad would become an accomplished sparkling wine producer in his own right. His winemaker, Charles Krug, would eventually buy land north of St. Helena to start his own winery, thus ushering in the Napa wine industry. Agoston’s winery, Buena Vista, would be bonded state winery #1. However, Agoston’s most controversial contribution was the introduction of California’s most celebrated “native” grape–Zinfandel. Son Arpad insisted that his father purchased the vines from friend, and fellow Hungarian ex-patriot, Làzàr Mészàros in 1852 who resided in New Jersey at the time. Others, most notably Charles Sullivan, dispute this claim and have evidence the grape appeared in CA long before that. Since recent DNA evidence now links Zinfandel to a Croatian grape (Crljenak Kastelansk), at least the Hungarian connection seems plausible. Regardless, with Zinfandel at the forefront the race to make better quality wine was on.

Whatever happened to Agoston? Always the opportunist, even in his seventies he never gave up. He moved to Nicaragua to start a rum distillery. Unfortunately, this is where the story ends rather tragically. His wife died of yellow fever and one of his sons, who didn’t like the climate, died on the sail back to San Francisco. Around the same time as his son’s death, Agoston himself “disappeared” after falling into an alligator-infested river and was never found.

Long live the Prince!

In my next chapter we’ll explore the rise and fall of the wine boom of the 1800s from end of the Gold Rush to the depression of 1893.”