The Dry Years

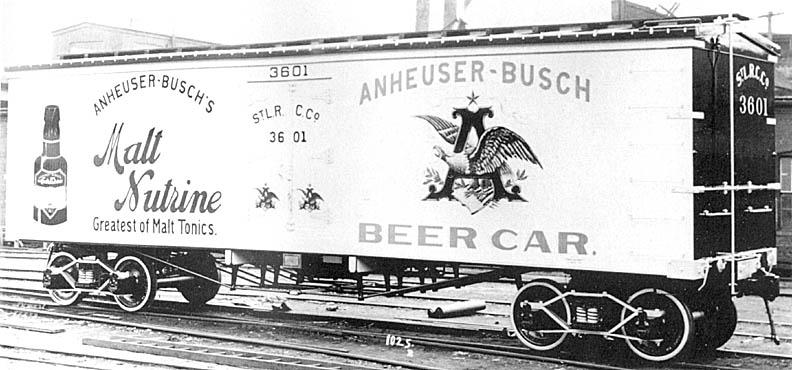

As I mentioned in my last post, the Gilded Age of the late 1800s were a boom for California’s wine industry. The combination of the gold rush, transcontinental railroads, and phylloxera infestation of European vineyards gave the California wine industry a real boost. However, starting with the panic, and ultimate depression, of 1893 the American wine industry as a whole was stricken with all sorts of calamities. The late 1800s also saw inventions like refrigeration, pasteurization, and the bottle cap… and thus, the rise of “American Lager.” Unlike the English, most Americans didn’t develop a taste for hopped ale. Much of the beer made in America was a lighter style lager made by German immigrants like Miller and Busch. Before pasteurization and without the preserving quality of hops, lager had a limited lifespan and needed to be consumed where they were made. In California German immigrant Gottlieb Brekle established Anchor Steam brewery in San Francisco utilizing its naturally cold, foggy nights to cool fermentation. Pasteurization and the bottle cap made beer portable. Any American with an ice box could pop a cold one in the comfort of their own home. In short order, beer became our preferred beverage. A statistic that has only recently diminished.

Enter Prohibition

Neither beer nor wine could withstand the dreaded 18th amendment. Prohibition brought an end to commercial production of all alcoholic beverages. The law was so strict that on passing all adult beverage establishments were supervised as they dumped and destroyed all their existing stock. Many creeks in Sonoma and Napa turned red on that day in January, 1920. Confronted with financial disaster, most wineries closed down in defeat. However, unlike beer and spirits, for the intrepid wineries there were a couple options available within the constraints of the law that would permit some to survive. Churches were still allowed to serve sacramental wine and wineries were permitted to sell it to them. Of course, this was not a large market, but Catholic Italian-owned wineries like Sebastiani and Simi in Sonoma had an inside tract. This business was not unlike medicinal marijuana today. Needless to say, during prohibition sacramental wine demand went up exponentially.

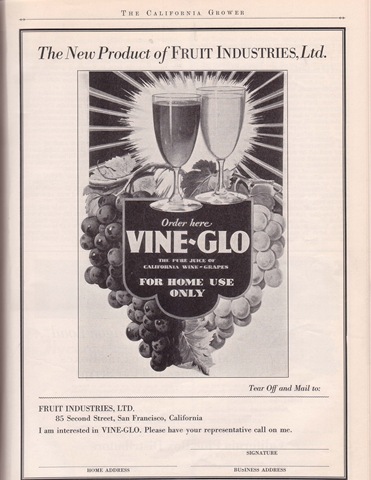

The laws of prohibition also allowed up to 200 gallons per year, per family of wine for home use. Since most consumers didn’t grow grapes on their property many wineries had developed a novel new product commonly called “Vine-Glo.” This was essentially unfermented grape juice sold direct to consumers with a rather dubious label on each bottle,

Warning: do not store a full bottle of this product in a cool, dark place for 60-80 days or it will ferment and become alcohol.

The original branded version of Vine-Glo was produced by a company called Fruit Industries in the late 1930s and was so popular it raised the ire of Al Capone and the Federal Government alike. Some California wineries-cum-fruit juice companies were producing copycat products including a small Lodi operation called Caesar Mondavi and Co (Caesar was Robert and Peter Mondavis’ father).

The eventual repeal of Prohibition in 1933 brought a rush of new wine entrepreneurs to Napa and Sonoma. However, something happened to the American palate along the way. The East Coast elite were back to drinking French wine (which they had been smuggling during prohibition). Middle class Americans who didn’t drink lager had a discovered a new beverage while drinking at illegal Speak Easys called the “cocktail.” Until prohibition most spirits were palatable enough to drink straight from a shot glass. Illegal spirits like “bathtub gin” were not so–and often times downright poisonous! So, bartenders would mix in fruit juice, sodas, and tonics to make their consumption possible. The new concoctions even made spirits, which were largely a manly drink, appealing to women. Prohibition had not only reduced Americans’ thirst for adult beverages, but had inadvertently introduced new choices. Wine’s broad appeal was waning.

New post-prohibition wineries closed down almost as fast as they opened. Survivors had to figure out a way to adapt. The most popular method was to reduce price and sell in bulk in order to be more competitive with beer and other beverages. “Jug” wine was the antithesis of what pioneers Simi, Niebaum, Harazthy, and Krug were promoting, but these were desperate times. One new post prohibition wine family came to understand this more than any other. In my next chapter we’ll explore how the Gallo family established a new genre of winemaking in Sonoma County.